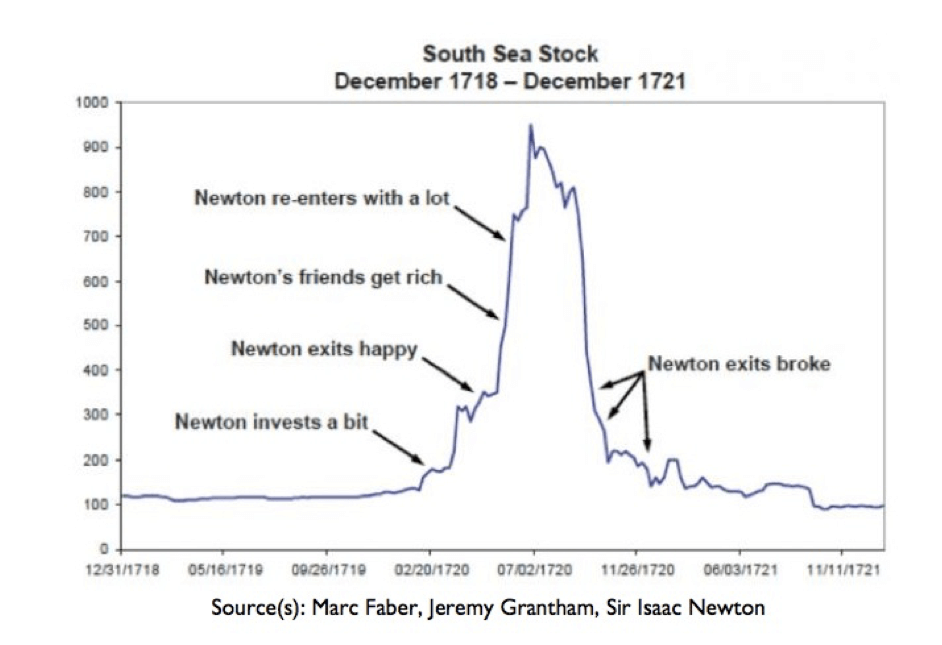

In the late spring of 1720, Sir Isaac Newton decided to sell his stocks.

Newton had been an investor in the South Sea Company, a famous enterprise which effectively commanded a trading monopoly with South America.

The investment had already made Newton a lot of money, he was up more than 100% in a very short time.

In fact, investors were clamoring to buy up the South Sea Company’s stock, and the share price kept climbing. And climbing.

Newton sensed that the market was getting overheated. It no longer made sense to him. So he sold.

There was only one problem: the share price of the South Sea Company kept climbing.

All of Newton’s friends were getting rich. So, against his better judgement, Newton went back in, repurchasing shares at more than three times the price of his original stake.

The market then collapsed, and he lost virtually all his life savings.

The experience is said to have given rise to his bemused response:

“I can calculate the movement of stars, but not the madness of men.”

* * *

It’s now been roughly ten years since the Global Financial Crisis began.

In the time-honoured manner of regulators, they waited until the battle was largely over, then waded onto the battlefield and shot the survivors.

The decade since has seen unprecedented monetary stimulus, i.e. central bankers have expanded their various money supplies by trillions upon trillions of dollars, giving rise to a massive bubble in asset price worldwide.

Stocks are at all-time highs. Bonds are at all-time highs. Property prices are at all-time highs. Many alternative assets like private equity and collectibles are at all-time highs.

Yet asset prices keep climbing.

Perhaps desperate to avoid the mistakes of Isaac Newton, Scotsman Hugh Hendry, founding partner of Eclectica Asset Management, has recently announced that he is closing his hedge fund.

Hendry is a famous critic of this monetary absurdity and consequent asset bubble.

“It wasn’t supposed to be like this.. markets are wrong,” Hendry told investors.

Of course, the market is under no obligation to be right. Ever.

Hendry’s view is accurate– nearly every objective metric shows that the market is incredibly overpriced.

Clint Eastwood’s infamous character Dirty Harry once remarked that a man needs to know his limitations. We think we know at least some of ours: we can’t time markets.

And the only thing we know with any certainty, as sure as night follows day, is that there are always corrections– both booms AND busts.

A decade’s worth of QE and ZIRP has fuelled a runaway train, and at some point there will be a correction.

Does it make sense to stand in front of the train? Or is it better to, as Isaac Newton did, leap aboard for some final thrills?

We prefer neither.

Instead we’re diversifying as pragmatically as we can, working diligently to find undervalued companies run by honest, talented managers.

It requires more hard work and patience than buying some overpriced index fund or whatever the popular investment du jour happens to be.

But nobody ever said this investing business was supposed to be easy.

Earlier this year my publishers invited me to write the foreword to their definitive edition of Reminiscences of a Stock Operator, a thinly disguised biography of the legendary trader Jesse Livermore.

Livermore was extraordinary. Born in 1877, Livermore ran away from home as a child and soon began trading stocks.

By the time he was 20, he had already amassed a fortune of $3 million, more than $75 million in today’s money.

Livermore sold short, i.e. bet that stock prices would fall, just prior to the 1907 crash, as well as the 1929 crash.

His bets were so lucrative that, going into the Great Depression, Livermore had a fortune of more than $100 million, or about $1.4 billion today.

But Livermore wasn’t just great at making money from overheated markets. He was also a master of losing money.

This book is widely and rightly regarded as an investment classic. It is also crammed with valuable observations about the practice of speculation and successful trading.

Among them, the importance of being patient and disciplined:

“After spending many years in Wall Street and after making and losing millions of dollars I want to tell you this: It never was my thinking that made big money for me. It was always my sitting.”

Sitting. As in, doing nothing. As in… neither standing in front of the train, nor jumping on board.

Hedge fund managers like Hugh Hendry don’t have this option. They have to be invested. They have to report to their investors every quarter… and if they’re not making money, investors bail.

But as an individual, you are not accountable to anyone but yourself.

So you are free to sit… and patiently wait for the safe, compelling investments that will arise once market conditions return to sanity.

Do you have a Plan B?

Credit to Zero Hedge

No comments:

Post a Comment