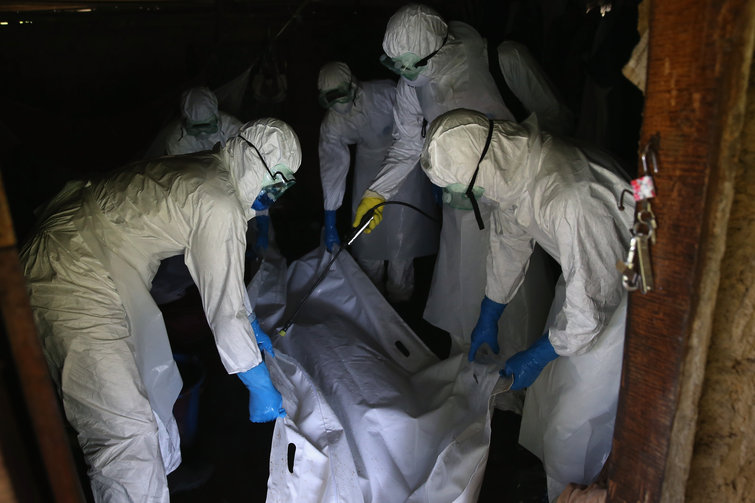

John Moore/Getty Images

Earlier today, the Liberian government published a list of the supplies it has on hand to treat Ebola patients — and the supplies it thinks it will need. The data paints a dire picture of a country bracing for an outbreak that only gets worse.

The Liberian government estimates it needs an additional 84,841 body bags. It currently has 4,901 on hand.

The West African country also needs more than 2 million boxes of rubber gloves and a half-million pairs of goggles and tens of thousands more pairs of rubber boots. Right now, it has very little of any of these. You can see the gap between supplies needed and supplies on hand here:

The full list of supplies, both those on hand and those necessary, is available in the government’s most recent situation report.

(Liberian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare)

Liberia has been harder hit by the Ebola outbreak than any other country. It has so far recorded 4,076 cases and 2,316 deaths. More than half of all Ebola deaths worldwide have happened in Liberia.

The country is also poor, with few resources to fight the deadly outbreak. Even before Ebola hit, Liberia had one of the world’s poorest health care systems. Liberia spends an average of $66 per person per year on health care — a mere 2 percent of the OECD average.

Earlier today, the Liberian government published a list of the supplies it has on hand to treat Ebola patients — and the supplies it thinks it will need. The data paints a dire picture of a country bracing for an outbreak that only gets worse.

The Liberian government estimates it needs an additional 84,841 body bags. It currently has 4,901 on hand.

The West African country also needs more than 2 million boxes of rubber gloves and a half-million pairs of goggles and tens of thousands more pairs of rubber boots. Right now, it has very little of any of these. You can see the gap between supplies needed and supplies on hand here:

The full list of supplies, both those on hand and those necessary, is available in the government’s most recent situation report.

(Liberian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare)

Liberia has been harder hit by the Ebola outbreak than any other country. It has so far recorded 4,076 cases and 2,316 deaths. More than half of all Ebola deaths worldwide have happened in Liberia.

The country is also poor, with few resources to fight the deadly outbreak. Even before Ebola hit, Liberia had one of the world’s poorest health care systems. Liberia spends an average of $66 per person per year on health care — a mere 2 percent of the OECD average.

Supplies matter a lot in the Ebola outbreak. Without proper protective gear, its easier for the disease to spread — not just in Liberia, but also outside of the country, too.

If you’re looking for ways to help ease the supply shortage, consider this list of non-profits currently providing aid in West Africa in the Ebola fight.

Hat tip to the Washington Post for noticing this report earlier today.

Card 6 of 12 Launch cards

For every four cases of Ebola we know of, there might be six that we don’t

While official estimates suggest there are already more than 8,000 cases of Ebola this year, the real number is likely much, much higher. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that the actual number of Ebola cases is roughly 2.5 times higher than the reported figures — so for every four Ebola cases we know of, there could be six that we don’t.

The CDC isn’t alone in this. “There is widespread under-reporting of new cases,” warns the World Health Organization. The WHO has continually said that even its current dire numbers don’t reflect the full reality. The estimated 8,000-plus Ebola cases in West Africa could just be the tip of the iceberg.

Health workers sterilize the house and prepare a body for burial in Lango village, Kenema, Sierra Leone. (Photo courtesy of Andalou Agency)

To understand how an Ebola case could be missed, you need to understand what it takes to actually find and count a case.

Often times, potential cases are communicated through dedicated hot-lines, which citizens can call in to report on themselves or their neighbors. Health workers or doctors can call in cases, too. These reports are forwarded to local surveillance response teams.

All these cases need to be followed up on and verified to be counted. To do that, a team of two to four investigators is dispatched to hunt for the suspected Ebola victim.

Tracking down Ebola cases is difficult in places where the roads and communication infrastructure are poor.

Actually tracking these people down isn’t straightforward, especially in areas where the roads and communication infrastructure are poor. Investigators can spend days chasing a rumor.

These health teams also work under constant stress and uncertainty. During this outbreak, they’ve faced violence, angry crowds, and blockaded roads. They can’t wear protective gear because they’ll scare off locals.

When they finally locate an Ebola victim, he or she may not always be lucid enough to talk or even still alive. So the investigators need to interview friends, family or community members to determine whether it’s Ebola that struck — always keeping a distance.

If this chase appears to have led to an Ebola patient, the health team notifies a dispatcher to have that person transported by ambulance to a nearby clinic or Ebola treatment center for testing and isolation.

If the person is already dead, they notify a burial team, which arrives in full personal protective gear. They put the body in a body bag, decontaminate the house, swab the corpse for Ebola testing, and transport the body to the morgue.

But confirming the cause of death doesn’t always happen. There have been reports that mass graves hold uncounted Ebola cases. With limited resources, too, saving people who are alive tends to take precedent over managing and testing dead bodies.

Reported cases are then communicated to the ministry of health in the country. These reports are combined with counts from NGOs and other aid organizations working in the region. The numbers come in three forms: lab-test confirmed cases, suspected cases, and probable cases. The WHO classifies a suspected case as an illness in any person, dead or alive, who had Ebola-like symptoms. A probable case is any person who had symptoms and contact with a confirmed or probable case.

The ministry of health compiles and crunches this information and sends it to the WHO country office. They then report that to the WHO’s regional Africa office in Brazzaville, Congo and that message is passed along to Geneva, home to WHO’s headquarters.

“At each step along the way the case can fall out of the pool of ‘counteds.'”

To get to this point, Dr. David Fisman, an infectious disease modeler working on Ebola, summed up: “A person needs to have recognized symptoms, seek care, be correctly diagnosed, get lab testing — if they’re going to be a confirmed case — have the clerical and bureaucratic apparatus actually transmit that information to the people doing surveillance. At each step along the way the case can fall out of the pool of ‘counteds.'”

12 things you need to know about Ebola 12 Cards / Edited By Julia BelluzUpdated Oct 17 2014, 4:57p

In this StoryStream

Ebola outbreak: the deadliest in history

Oct 16

Watch: Nurse with Ebola posts video from her Dallas hospital room

Oct 15

Liberia thinks it needs 84,000 more body bags for the Ebola outbreak

Oct 15

Nurses are furious, may picket, over inadequate Ebola training

93 updates

Credit to Common Sense

If you’re looking for ways to help ease the supply shortage, consider this list of non-profits currently providing aid in West Africa in the Ebola fight.

Hat tip to the Washington Post for noticing this report earlier today.

Card 6 of 12 Launch cards

For every four cases of Ebola we know of, there might be six that we don’t

While official estimates suggest there are already more than 8,000 cases of Ebola this year, the real number is likely much, much higher. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that the actual number of Ebola cases is roughly 2.5 times higher than the reported figures — so for every four Ebola cases we know of, there could be six that we don’t.

The CDC isn’t alone in this. “There is widespread under-reporting of new cases,” warns the World Health Organization. The WHO has continually said that even its current dire numbers don’t reflect the full reality. The estimated 8,000-plus Ebola cases in West Africa could just be the tip of the iceberg.

Health workers sterilize the house and prepare a body for burial in Lango village, Kenema, Sierra Leone. (Photo courtesy of Andalou Agency)

To understand how an Ebola case could be missed, you need to understand what it takes to actually find and count a case.

Often times, potential cases are communicated through dedicated hot-lines, which citizens can call in to report on themselves or their neighbors. Health workers or doctors can call in cases, too. These reports are forwarded to local surveillance response teams.

All these cases need to be followed up on and verified to be counted. To do that, a team of two to four investigators is dispatched to hunt for the suspected Ebola victim.

Tracking down Ebola cases is difficult in places where the roads and communication infrastructure are poor.

Actually tracking these people down isn’t straightforward, especially in areas where the roads and communication infrastructure are poor. Investigators can spend days chasing a rumor.

These health teams also work under constant stress and uncertainty. During this outbreak, they’ve faced violence, angry crowds, and blockaded roads. They can’t wear protective gear because they’ll scare off locals.

When they finally locate an Ebola victim, he or she may not always be lucid enough to talk or even still alive. So the investigators need to interview friends, family or community members to determine whether it’s Ebola that struck — always keeping a distance.

If this chase appears to have led to an Ebola patient, the health team notifies a dispatcher to have that person transported by ambulance to a nearby clinic or Ebola treatment center for testing and isolation.

If the person is already dead, they notify a burial team, which arrives in full personal protective gear. They put the body in a body bag, decontaminate the house, swab the corpse for Ebola testing, and transport the body to the morgue.

But confirming the cause of death doesn’t always happen. There have been reports that mass graves hold uncounted Ebola cases. With limited resources, too, saving people who are alive tends to take precedent over managing and testing dead bodies.

Reported cases are then communicated to the ministry of health in the country. These reports are combined with counts from NGOs and other aid organizations working in the region. The numbers come in three forms: lab-test confirmed cases, suspected cases, and probable cases. The WHO classifies a suspected case as an illness in any person, dead or alive, who had Ebola-like symptoms. A probable case is any person who had symptoms and contact with a confirmed or probable case.

The ministry of health compiles and crunches this information and sends it to the WHO country office. They then report that to the WHO’s regional Africa office in Brazzaville, Congo and that message is passed along to Geneva, home to WHO’s headquarters.

“At each step along the way the case can fall out of the pool of ‘counteds.'”

To get to this point, Dr. David Fisman, an infectious disease modeler working on Ebola, summed up: “A person needs to have recognized symptoms, seek care, be correctly diagnosed, get lab testing — if they’re going to be a confirmed case — have the clerical and bureaucratic apparatus actually transmit that information to the people doing surveillance. At each step along the way the case can fall out of the pool of ‘counteds.'”

12 things you need to know about Ebola 12 Cards / Edited By Julia BelluzUpdated Oct 17 2014, 4:57p

In this StoryStream

Ebola outbreak: the deadliest in history

Oct 16

Watch: Nurse with Ebola posts video from her Dallas hospital room

Oct 15

Liberia thinks it needs 84,000 more body bags for the Ebola outbreak

Oct 15

Nurses are furious, may picket, over inadequate Ebola training

93 updates

Credit to Common Sense

No comments:

Post a Comment