Falling rates of global trade growth have attracted much comment by analysts and officials, giving rise to a literature on the ‘global trade slowdown’ (Hoekman 2015, Constantinescu et al. 2016). The term ‘slowdown’ gives the impression of world trade losing momentum, but growing nonetheless. The sense of the global pie getting larger has the soothing implication that one nation’s export gains don’t come at the expense of another’s. But are we right to be so sanguine?

World trade volume plateaued around January 2015

Using what is widely regarded as the best available data on global trade dynamics, namely, theWorld Trade Monitor prepared by the Netherlands Bureau of Economic Policy Analysis, the 19th Report of the Global Trade Alert, published today, evaluates global trade dynamics (Evenett and Fritz 2016). Our first finding that the rosy impression painted by some should be set aside. We demonstrate that:

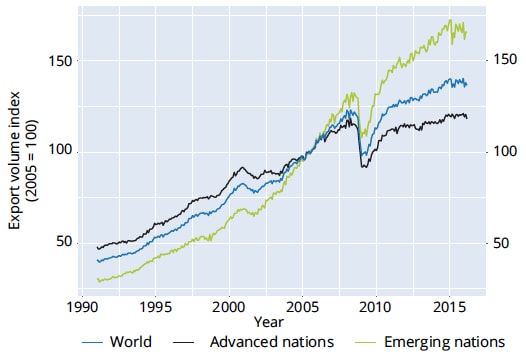

-World export volumes reached a plateau at the start of January 2015. The same finding holds if import volume or total volume data are used instead.-Both industrialised countries’ and emerging markets’ trade volumes have plateaued (Figure 1).

Figure 1 World trade plateaued around the start of 2015

-Except during global recessions, a plateau lasting 15 months is practically unheard of since the Berlin Wall fell.-In 2015 the best available data on world export volumes diverges markedly from that reported by the WTO, IMF, and World Bank, and probably explains why analysts at these organisations have missed this profound change in global trade dynamics (Table 1).Table 1 Marked differences in reported global trade volume growth in 2015

Image: VoX EU

Our argument is not that world trade has stopped. Rather, that according to a benchmark measure of trade volume, world trade isn’t slowing down – it is not growing at all.

More products accounts for the lion’s share of trade’s fall in 2015

So much for trade volumes, but what of the total value of world trade? Our last report showed that three oil-related products accounted for just over half of the fall in the value of world trade from October 2014 to June 2015 (Evenett and Fritz 2015). Coupled with the rising value of the US dollar, some felt that these factors – rather than a change in global trade dynamics – accounted for the falling value of world trade in 2015. Does this story fit the facts?

To examine the variation in trade flows across products during the global trade plateau, a detailed product-level dataset of the value of trade was assembled from the monthly UN trade data releases through to December 2015. Analysis of this dataset revealed that:

Falling commodity prices could not have accounted for the majority of the fall in the value of global trade in 2015. In fact, raw materials trade recovered partially in the fourth quarter of 2015.The total value of capital goods trade fell in the first half of 2015 and then plateaued; same for consumer goods.Meanwhile, parts and components trade fell in value throughout 2015.The pain is spreading – in our last report we showed that 28 product groups each accounted for 0.5% or more of the fall in the value of world trade. That number has now risen to 38.The product groups that contributed more to the fall in the value of world trade in 2015 faced policies skewed towards trade restrictions and away from subsidies and export incentives (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Products where trade fell the most in 2015 faced proportionally more trade restrictions

Image: VoX EU

In sum, the variation across products in how much trade fell in value in 2015 suggests that an across-the-board currency valuation effect (caused by the rising value of the US dollar) or a ‘commodities only’ story are not enough. That there could be a link between the policy mix facing a product on global markets and changing trade values begs the question as to whether trade policy dynamics changed during the global trade plateau as well. We turn to this matter.

Was 2015 unusual for trade policy dynamics too?

In a nutshell, yes. Using the latest update of the Global Trade Alert, which saw 1,016 new reports of government policy measures added to the database from mid-October 2014 to 1 May 2015, we found that:

Resort to protectionism in 2015 is 50% up on that seen in 2014.Policy initiatives harming foreign commercial interests in 2015 outnumbered trade liberalisation three-to-one.Since 2010 between 50 and 100 protectionist measures were implemented in the first four months of each year; in 2016 the total had exceeded 150.G20 members were responsible for 81% of protectionist measures implemented in 2015.

Before world trade plateaued, duties for dumping, subsidisation, and import surges were used most; during the plateau, trade-distorting bailouts and financial assistance were number one. Since global trade plateaued, another trade restriction – export taxes – were used less and requirements on investors to source locally imposed more often. In short, the policy mix used by governments appears to have shifted once trade plateaued, suggesting trade policy dynamics have evolved as well (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Top 10 most used harmful measures since the crisis began

Image: VoX EU

The new GTA report also includes a chapter on the high-profile trade policy tensions in the steel sector. Last year and this, steel sector interventions have been under the spotlight. However, our report shows that protectionism in this sector has been ratcheting up since 2010 and, while so much attention is focused on tariffs targeting dumped steel, in fact, state incentives to promote steel exports are a far larger systemic problem.

In contrast to high-profile steel, our report also includes a chapter on the quiet spread of old and newer forms of local content requirements. This development is remarkable in light of the widely held view that these measures were banned over 20 years ago in a WTO accord. Nevertheless, they have made a comeback and we draw out the key lessons from the growing body of analysis of the adverse trade, foreign direct investment, and welfare impact of rules that force firms to source locally.

Multinational firms are adjusting to the new reality of ever-more fragmented markets. As the CEO of General Electric recently put it: “A localization strategy can’t be shut down by protectionist politics” (Bhatia et al. 2016) Many more firms have announced plans to ‘localise production’. Since political leaders won’t rein in protectionism, pragmatic business people are adjusting – often by substituting foreign direct investment for trade.

Risk of a negative feedback loop

Either finding – of global trade growth coming to a halt or a sharp increase in beggar-thy-neighbour activity – ought to worry policymakers. That both coincide prompts questions of linkage. In our report we don’t claim to have shown definitely what is causing what – after all, multiple factors likely trade and policy decisions and the data available to check won’t be published for years.

Analysts have the luxury of waiting for data to mount up before taking a stand; decision-makers in the public and private sectors do not. As a result, going forward an even more important concern is that a negative feedback loop develops where zero trade growth fuels resort to even more zero-sum trade policies which, in turn, discourages cross-border supply of national markets.

In a world where global commerce isn’t growing any more, governments may conclude that larger market shares for their exporters can only be grabbed from trading partners. Parallel contests for talent, foreign direct investment, research and development hubs, and intellectual property would intensify. This could, in turn, precipitate a 21st century variant of mercantilism that, unlike its predecessors in earlier centuries, affects more types of global commerce.

Credit to Zero Hedge

No comments:

Post a Comment